Roman de Brut (Romance of Brutus) or Geste des Bretons (Deeds of the Britons) by Robert Wace of Jersey

Overview, Authorship, and Sources

Robert Wace of Jersey wrote this poem by AD 1155. Sometimes known as Brut, Charles Foulon calls it an inexact and expanded translation in Norman-French verse of Historia Regum Britanniæ. Gillette Labory and Henry Duff Traill tell us this work was also known as Brut d’Engleterre (Brutus of England) or Roman des Rois d’Angleterre (Romance of Kings of England), though Wace’s name for it was Geste des Bretons (Deeds of the Britons). Norris J Lacy claims Roman de Brut moves beyond a mere chronicle and approaches becoming a romance. It narrates a version of Britain’s story from its settlement by the Trojan refugee Brutus through a thousand years of quasi-pseudo-history up to the Roman conquest, the introduction of Christianity, the legends of post-Roman Britain, and ending with the reign of the 7th-Century AD King Cadwallader (Cadwaladr ap Cadwallon). According to James Jerome Wilhelm, the account of the life of King Arthur, the first in any vernacular language, is prominent. This account began and affected the whole of French Arthurian romances which include the Round Table and the bold undertakings of its various knights.

Born on the island of Jersey in the early 12th Century AD, Robert Wace was schooled at Caen and then in Paris. According to Ivor D O Arnold and Margaret M Pelan, Wace started writing Brut after he relocated to Caen. Françoise Hazel Marie Le Saux and Ivor Arnold tell us, at some point in this stage of his life, Wace visited southern England. Françoise H M Le Saux continues by stating while working under the patronage of Henry II, Wace presented a copy of his completed poem to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry’s wife. Roman de Brut’s popularity is shown from several extant manuscripts and its considerable sway over future writers. The main source for Roman de Brut’s content is Historia Regum Britanniæ by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Le Saux says it amplifies the reputation of British rulers at the cost of their Roman peers and includes a story of King Arthur’s reign. According to Charles Foulon, minor sources include “the Bible”, Life of Saint Augustine of Canterbury by Goscelin of Saint-Bertin, Historia Brittonum (History of Britons), Geoffrey Gaimar’s L’Estoire des Engleis (History of the English), Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of Kings of England) by William of Malmesbury, and the anonymous Gormond et Isembart (Gormond and Isembart).

Additions, Changes, and Omissions to Sources

Based on Breton tales with which he was familiar, Robert Wace made two important additions. J E Caerwyn Williams and Charles Foulon tell us one is the Round Table (its first existence in literature) and the other is the idea that Arthur now resides in Avalon. However, John Strong Perry Tatlock states there could be a different reason for giving Arthur a Round Table since there is good evidence to show that round or semi-circular tables were used before Robert Wace’s time for fabulous feasts. Charles Foulon, Jack Arthur Walter Bennett, and Judith Weiss claim certain changes Wace made in geographical details suggest he drew on his knowledge of Normandy, Brittany, and southern England. Wace omits a few contentious or partisan episodes from his sources, for example, the entirety of Book Seven of Historia Regum Britanniae, Merlin’s prophecies, which he says he will not translate because he does not understand them. Robert Wace also shortens or removes some passages of church history, expressions of exaggerated sentiment, and descriptions of barbarous or brutal behaviour. In battle scenes, according to Françoise H M Le Saux, Alan Lupack, Charles Foulon, and Judith Weiss, Robert omits some of the strategic particulars. Instead, he brings forth observations that evoke the pathos of war.

Wace gives Geoffrey’s tale an increased sharpness of clarity. Corinne Saunders and Laura Ashe tell us the characters have a more focussed motivation and individuality. Humour is injected and the role of the supernatural is downplayed. Wace adds dialogue and commentary to Historia’s narrative and modifies the work for its intended royal listeners. He gives specifics from both 12th-Century military life and palace happenings. Derek Pearsall claims the cumulative effect is for Wace to harmonise his story to the new chivalric and romantic climate of his day. According to Richard Cavendish, Françoise H M Le Saux, and Edmund Kerchever Chambers, Wace is diligent in highlighting the splendour of the court of King Arthur: the beauty of its ladies, gallantry of its knights, the relationship between Guinevere and Mordred, depth of Arthur’s love for Guinevere, grief over the deaths of his knights, and the knightly prowess of Gawain, Kay, and Bedivere. Alan Lupack, Ad Putter, and Françoise Le Saux tell us Robert Wace extended the story with expressive descriptions of passages such as Arthur’s sailing to Europe, the peace of twelve years amid his reign, and his conquests in Scandinavia and France. By these elucidations, says Karen Jankulak, Robert increased Arthur’s portion of the narrative from one-fifth of Historia to one-third of Brut.

Composition and Style

Robert Wace’s chosen metre of octosyllabic (eight-syllable) couplet was in the 12th Century AD usable for many purposes. Le Saux tells us Robert employed it in earlier writings, and in Brut utilised it with grace and clarity. John S P Tatlock and Ivor D O Arnold confirm Robert’s language was a literary form of Old French, Norman dialect. Wace was accomplished in the art of the phrase and rhythmic effects. Ivor D O Arnold, Gwyn Jones, and Charles Foulon claim Wace’s stylistic devices were antithesis, parallelism, repetition, and maxims. He had a large varied vocabulary and employed irony. While conforming to poetic art, he gave an appearance of spontaneity. According to J S P Tatlock, I D O Arnold, and Margaret M Pelan, Wace’s style was crisp, energetic, and unadorned. Roman de Brut is sometimes “excessively talkative”, says Gwyn Jones, but moderate by mediæval standards and Wace avoids the mediæval vice of exaggeration. Françoise H M Le Saux and Robert Huntington Fletcher tell us Wace distances himself from the narrative, adding his comments on the action. Le Saux goes on to say Wace confesses ignorance of what happened, but on minor details, thereby showing his authority on the essentials of his story. According to Charles Foulon and James J Wilhelm, Wace’s descriptions of nautical narratives, everyday scenes, and passages of drama are superb.

Resemblances and Imitations

Laura Ashe says the emphasis Robert Wace placed on the rivalries between knights and the role of love in their lives had an intense effect on writers of his own and later generations. Ivor D O Arnold and Penny Eley tell us Wace’s effects can be observed in a few of the earliest romances, including Renaut de Bâgé’s Le Bel Inconnu (The Fair Unknown), Le Roman d’Enéas (The Romance of Æneas), Gautier d’Arras’ Eracle and Ille et Galeron, and Benoît de Sainte-Maure’s Le Roman de Troie (The Romance of Troy). According to Charles Foulon and Frederick Whitehead, Thomas of Britain’s Roman de Tristan (Romance of Tristan) copies some of Roman de Brut’s historical specifics, such as the story of Gormon. Catherine Batt and Rosalind Field tell us Chrétien de Troyes adapts Geoffrey’s story of Mordred’s last campaign against Arthur in his romance of Cligès, and, as Ivor D O Arnold says, various passages in Roman de Brut contribute to Chrétien’s account of celebrations and other similar activities at Arthur’s court in Érec et Énide. Arnold goes on to tell us there are echoes of Roman de Brut in Philomela and Guillaume d’Angleterre (William of England), two poems sometimes attributed to Chrétien. Charles Foulon and Ernest Hoepffner say Marie de France had read Robert Wace, but are less certain how many passages in her Lais show its influence (the raids by the Picts and Scots in Lanval being obvious).

Two of the Breton Lais written in emulation of Marie de France exhibit obvious indications of owing gratitude to Roman de Brut. Hoepffner goes on to say Brut gave to Robert Biket’s Le Lai du Cor (The Lay of the Horn) certain elements of its style and several circumstantial details, and the anonymous Melion several plot-points. According to Félix Lecoy, Tintagel’s inclusion in La Folie Tristan d’Oxford (The Madness of Tristan) reflects particulars from Brut. In the early/mid 13th -Century, Meriadeuc, or Le Chevalier aux Deux Épées (Meriadoc, or The Knight of the Two Swords) was still demonstrating the influence Brut could exert. Margaret M Pelan tells us, in this instance, the author appears to be influenced by Wace’s narrative of Arthur’s birth, character, battles, and death. Edward Donald Kennedy says Robert de Boron derived Merlin from Roman de Brut, with some specifics from Historia Regum Britanniae. While Charles Foulon tells us de Boron counted on Brut for his Didot-Perceval. The story of Robert de Boron’s Merlin was continued in the Vulgate Suite du Merlin (Continuation of Merlin), which chooses, according to Alexandre Micha, Wace’s narrative when describing Arthur’s Roman war. Foulon and Jean Frappier claim the finale of the Vulgate’s Morte Artu (Death of Arthur) takes its narrative from Wace’s account of the end of Arthur’s reign, and his impact is also felt in Le Livre d’Artus (The Book of Arthur). According to Edward Donald Kennedy and Robert Huntington Fletcher, Je(h)an de Wavrin’s Recueil des C(h)roniques et Anc(h)iennes Istories de la Grant Bretaigne (Compendium/Collection of Chronicles and Ancient Histories of the Great/Grand Britain/Britons) bases its British history (up to the beginning of the Arthurian period) from an anonymous French adaptation of Wace’s Brut dating from c AD 1400, with substantial additions taken from the romances.

Influences of Roman de Brut and the additional Bruts

Around AD 1200, a Worcestershire priest named Layamon wrote a Middle English poem on British history which was to a great extent based on Roman de Brut though with some omissions and additions (the first of Wace’s Brut in English). G T Shepherd and Karen Jankulak tell us additional Bruts took an increasing amount of material from Wace. In the second half of the 13th Century AD, the Anglo-Norman Chronicle of Peter of Langtoft (Pierre/Piers de Langtoft) gave forth a modification of Wace’s Brut. Near the end of the 13th Century, the Prose Brut was written in Anglo-Norman. It took its content from Wace’s Roman de Brut and Estoire des Engleis by Geoffrey Gaimar. It resurfaced multiple times in the following years in altered and expanded versions, a few in Middle English. According to Françoise Hazel Marie Le Saux and John Anthony Burrow, at least 240 manuscripts of its various recensions are known, demonstrating its immense popularity.

Alan Lupack and Jack Arthur Walter Bennett tell us Robert Mannyng, in 1338, produced a lengthy verse, Chronicle which, for its first 13,400 lines, adheres close to Robert Wace’s Roman de Brut before introducing elements from other sources, such as Pierre (Piers) de Langtoft’s The Chronicle. Lesley Johnson and John J Thompson say another translation of Wace’s Brut, in Middle English prose, was written in the late 14th Century AD and is preserved in the College of Arms MS Arundel XXII. According to Alan Lupack and Lesley Johnson, Mannyng’s Chronicle, and Wace’s and Layamon’s Bruts are included in the sources which have been advocated for the late 14th-Century Alliterative Morte Arthure. In the Liber Rubeus Bathoniae manuscript, a late 14th/early 15th Century romance (Arthur) appears to be derived from a form of Roman de Brut enlarged with a few pieces from Layamon’s Brut and the Alliterative Morte Arthure, says Karen Hodder. Charles Foulon’s confirmation of the dates of Wace manuscripts shows he remained popular in England into the 14th Century, but from the 15th Century onward his readership faded away.

Manuscripts

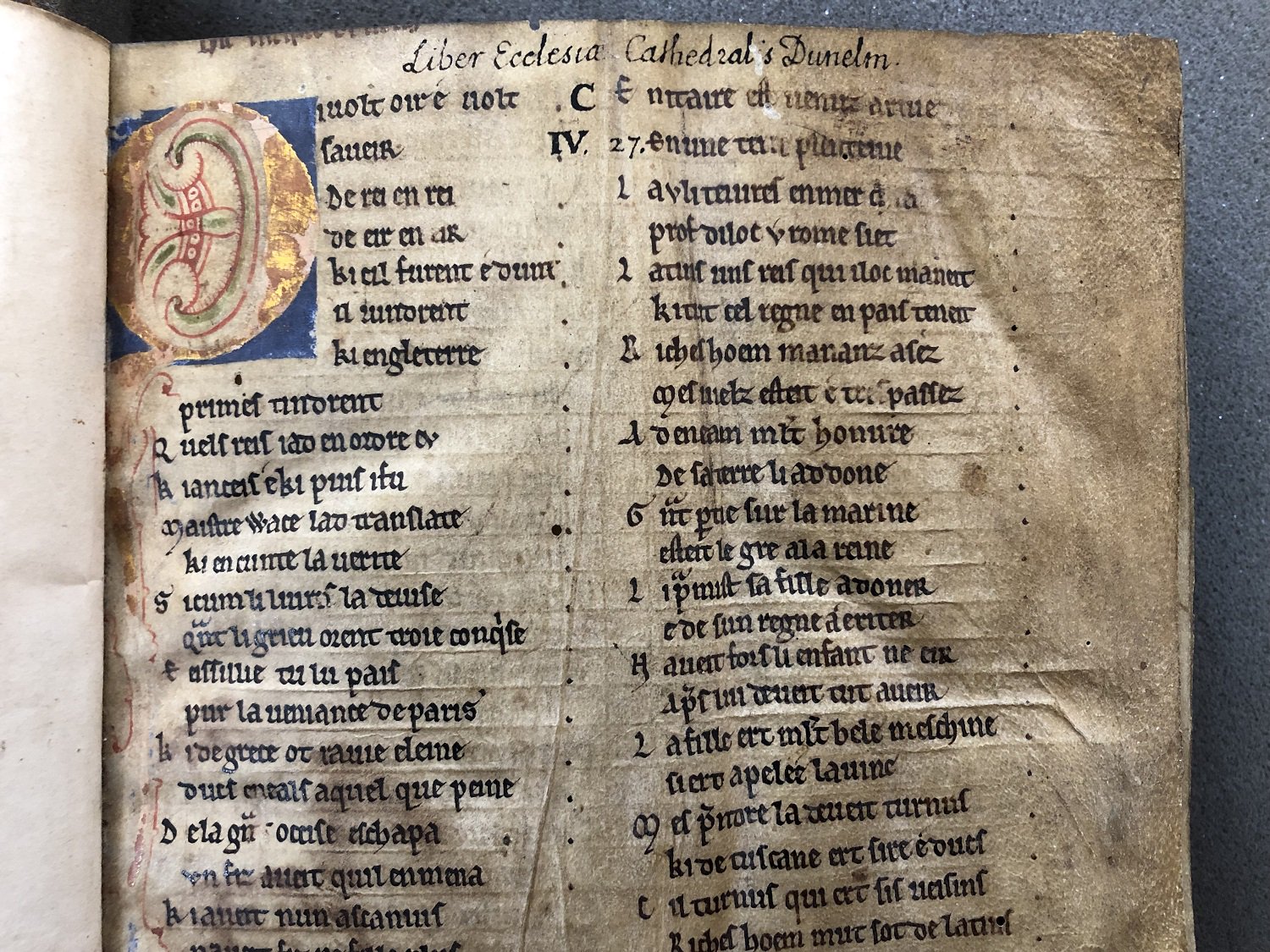

Greater than thirty manuscripts of Roman de Brut are extant. As time goes on, more fragments are discovered. Françoise H M Le Saux and Charity Urbanski tell us manuscripts were produced in equal numbers in England and France, demonstrating it was a popular work in both countries. Le Saux goes on to say nineteen of these manuscripts give a more or less complete text of the poem, of which the two oldest are Durham Cathedral MS C iv 27 (late 12th Century AD) and Lincoln Cathedral MS 104 (early 13th Century). Both of these manuscripts form an almost continuous story of Britain’s history from Brutus the Trojan’s arrival to the reign of Henry II, continues Le Saux. Initial readers of Roman de Brut believed it to be real history. Subsequent manuscripts encompass Arthurian romances as opposed to chronicles, illustrating Roman de Brut was seen later as somewhat less historical.

Conclusion

By AD 1155, Robert Wace of Jersey had written Roman de Brut. Also known as Brut d’Engleterre or Roman des Rois d’Angleterre, Wace’s name for it was Geste des Bretons. Sometimes known as Brut, it moves beyond a mere chronicle and approaches becoming a romance. The poem narrates a quasi-pseudo-fictional version of Britain’s history from its settlement by the Trojan Brutus through a thousand years of the story up to the Roman conquest, the introduction of Christianity, the legends of post-Roman Britain, and ending with the reign of 7th-Century King Cadwallader. The main source for Roman de Brut’s content is Historia Regum Britanniæ. Minor sources include “the Bible”, Life of Saint Augustine of Canterbury, Historia Brittonum, L’Estoire des Engleis, Gesta Regum Anglorum, and Gormond et Isembart. Wace added two ideas: the Round Table and Arthur residing in Avalon. Robert Wace’s effects can be observed in Le Bel Inconnu, Roman d’Enéas, Eracle, Ille et Galeron, and Roman de Troie. Various Bruts were written based on Roman de Brut. Around AD 1200, Layamon wrote a Middle English poem on British history, Brut. Near the end of the 13th Century, the Prose Brut was written in Anglo-Norman. The Chronicle of Peter of Langtoft (Pierre/Piers de Langtoft) gave forth a modification of Wace’s Brut. In 1338, Robert Mannyng produced a lengthy verse Chronicle that adheres close to Robert Wace’s Roman de Brut. Another translation of Wace’s Brut, into Middle English prose, was written in the late 14th Century. Initial readers of Roman de Brut believed it to be real history. Later, it was seen as somewhat less historical. Not only did Robert Wace of Jersey inspire later Bruts, but he also gave us the Round Table and the idea King Arthur still lives in Avalon.