Welcome to our article on De Gestis Britonum, or Historia Regum Britanniae, otherwise known as the Deeds of Britons, or History of Kings of Britain

Introduction to and Value of the Text

Originally called De Gestis Britonum (On Deeds of Britons), Historia Regum Britanniae (History of Kings of Britain) is a quasi-pseudo-historical chronicle of British history. It was written c AD 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It accounts for the lives of the kings of the Britons throughout two millennia, commencing with the Trojans founding of Briton and continuing until the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians took control of much of the island c late 6th/early 7th Centuries AD.

It is one of the central portions of the “Matter of Britain”. Although taken as purely historical well into the 16th Century, it is now considered by most to have absolutely no value as history, yet by many others to have small “kernels” of truth strewn throughout the text. Polydore Vergil’s disbelief of Geoffrey of Monmouth provoked a reaction of denial in England, “yet the seeds of doubt once sown” eventually replaced Geoffrey’s romanticized notions with a new revival of historical approach, according to Hans Baron’s, “Fifteenth-century civilization and the Renaissance” in The New Cambridge Modern History.

When events described, such as Julius Cæsar’s invasions of Britain, can be verified from contemporary accounts, Geoffrey’s “history” can be seen as wildly incorrect. Historia remains, however, a valuable piece of mediæval literature, which contains the earliest known version of the story of King Lear and his three daughters, and it helped to popularize the legend of King Arthur.

Geoffrey’s Inscription and Dedicatory

He starts the text with a statement of purpose in writing Historia (paraphrased as): I have not been able to discover anything at all about the kings who lived here before the Incarnation of Christ, or indeed about Arthur and all the others who followed after the Incarnation. Yet the deeds of these men are such that they deserve to be extolled for all time. Geoffrey purports to have been given a source for this period by Archdeacon Walter of Oxford: a “certain very ancient book written in the British language” from which he has translated Historia.

He also cites Gildas and Bede as sources. There follows, according to Lewis G M Thorpe, a dedication to Robert, Earl of Gloucester and Waleran, Count of Meulan, whom Geoffrey enjoins to use their knowledge and wisdom to improve his tale. In most modern translations, this section appears before “Book I”. Spellings used are mostly Geoffrey’s.

Book I (after the Dedication) – Brutus Occupies the Island of Albion

The following recounted events utilise Lewis Thorpe’s 1966 translation and John Allen Giles’ of 1842. The story begins when the Trojan Aeneas’ supposéd grandson Brutus is banished, after killing his parents. He journeys to Greece; then writes a letter to King Pandrasus. Brutus attacks the forces of Pandrasus by surprise. He routs them and takes Antigonus (the brother of Pandrasus), along with Anacletus, as a prisoner. Sparatinum is besieged by Pandrasus. Those besieged ask Brutus for assistance. Fearing death, Anacletus betrays the army of the Greeks. King Pandrasus is taken prisoner. It is discussed what is to be done with him. Pandrasus gives his daughter Ignoge in marriage to Brutus, who then leaves Greece. After a period of wandering, Brutus finds a desert island where he is directed by the Goddess Diana (via her Oracle) to settle on an island in the western ocean. Brutus lands at what is now Totnes (in Devon). He names the island, then called Albion, “Britain” after himself. The island is divided between Brutus and Corineus. Brutus defeats the giants who are the only inhabitants of the island, and establishes his capital, Troia Nova (New Troy), on the banks of the Thames; after his time it is renamed London and sometimes referred to as the City of Logres. New Troy being built, and the laws made for the government of it, it is given to its citizens that were to inhabit it.

Books II and III – Before the Romans Came

Book II – From the Death of Brutus to the Rise of Dunvallo Molmutius

When Brutus dies, his three sons, Locrinus, Kamber and Albanactus, divide the country between themselves; the three kingdoms are named Loegria (geographically occupying what is now England), Kambria (the area that would eventually become Wales), and Albany (that which is present-day Scotland). Locrinus, after routing Humber, falls in love with Estrildis. Corineus resents the affront put upon his daughter, Guendolœna. Locrinus, at last, marries Guendolœna. When he is killed, Estrildis and Sabre are thrown into a river. Guendolœna delivers up the kingdom to Maddan, her son, after whom succeeds Menptricius. The story then progresses rapidly through the reigns of the descendants of Locrinus (Ebraucus, a later Brutus, Leil, and Hudibras), including Bladud (son of Hudibras), who uses magic and even tries to fly, but dies in the process. Bladud’s son Leir (Lear) reigns for sixty years. Leir has no sons, so upon reaching old age he decides to divide his kingdom among his three daughters: Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. To decide who should get the largest share, Leir asked his daughters how much they loved him. Goneril and Regan give extravagant responses, but Cordelia answered plainly and sincerely; angered, Leir gave Cordelia no land. Goneril and Regan shared half the island with their husbands, the Dukes of Albany and “Cornwall”. Cordelia married Aganippus, King of the Franks, and left for Gaul.

Soon Goneril, Regan, and their husbands rebel and take the whole kingdom. After Leir has had all his attendants taken from him, he begins to regret his actions toward Cordelia and travels to Gaul. Cordelia accepts him with compassion and restores his royal attire and entourage. By Aganippus, a Gaulish army is raised for Leir, who returns to “Britain”, conquers his sons-in-law, and obtains the kingdom. Leir rules for three years and then dies. Cordelia inherits the throne to rule for five years before Marganus and Cunedagius, her sisters’ sons, rise against her. They imprison Cordelia; grief-stricken, she kills herself. Marganus and Cunedagius divided the kingdom between themselves. They soon quarrelled and went to war with each other. Cunedagius eventually kills Marganus in Kambria and retains the whole kingdom, ruling for thirty-three years. He is succeeded by his son Rivallo. A descendant of Cunedagius, King Gorboduc, had two sons called Ferreux and Porrex. They quarrelled and both were eventually killed. This sparked a civil war and led to “Britain” being ruled by five kings (who kept attacking each other). Dunvallo Molmutius, son of Cloten, the King of “Cornwall”, becomes pre-eminent. Eventually defeating the other kings, Dunvallo establishes his rule over the entire island. It is said that he instituted the “Molmutine Laws” which are still celebrated today among the English.

Book III – From Civil War to the Renaming of New Troy

Belinus and Brennius, the sons of Dunvallo, fight a civil war. Brennius marries the daughter of the King of the Norwegians. Brennius fights King Guichthlac of the Dacians. Guichthlac and Brennius’ wife are driven ashore and taken by Belinus. Belinus routs Brennius (who flees to Gaul). The King of Dacia, along with Brennius’ wife, is released from prison. Belinus reviews and confirms the Molmutine Laws. Brennius, as Duke of the Allobroges, returns to “Britain” to fight with his brother. The two brothers are reconciled by their mother and propose to subdue Gaul. The victorious brothers march to Rome. Brennius remains in Rome (and besieges it) after the Romans make and then break a covenant with him, while Belinus returns to rule “Britain”. Brennius is a tyrant to the Romans. Numerous brief accounts of successive kings follow (Gurgiunt Brabtruc, Guithelia, Morvidus, Gorbonian, Arthgallo, Elidure, Peredure, and Heli). These kings include Lud. He renames Trinovantum (Troia Nova) as “Kaerlud”, after himself. This name is later corrupted to “London”. Because Lud’s sons Androgeus and Tenvantius are not yet of age, Lud is succeeded by Cassibelanus (his brother). In recompense, Androgeus is made Duke of Kent and “Kaerlud” (formerly Trinovantum), and Tenvantius is made Duke of “Cornwall”.

Book IV – The Coming of the Romans

After his conquest of Gaul, Julius Cæsar looks over the sea and resolves to order Britain to swear obedience and pay tribute to Rome. Cassivellaunus sends a letter of refusal as an answer to these commands. Cæsar sails a fleet to Britain, but he is overwhelmed by Cassivellaunus’ army and forced to retreat to Gaul. Two years later he makes another attempt but is again pushed back. Then Cassivellaunus quarrels with one of his dukes, Androgeus, who sends a letter to Cæsar asking him to help avenge the duke’s honour. Cæsar invades once more and besieges Cassivellaunus on a hill. After several days, Cassivellaunus offers to make peace with Cæsar; and Androgeus, filled with remorse, goes to Cæsar to plead with him for mercy. Cassivellaunus pays tribute and makes peace with Cæsar, who then returns to Gaul. Because Androgeus had gone to Rome, when Cassivelaunus dies, he is succeeded by his nephew Tenvantius. Tenvantius is succeeded in turn by his son Kymbelinus, and then Kymbelinus’ son Guiderius. Emperor Claudius invades Britain because Guiderius refused to pay tribute. After Guiderius is treacherously killed in battle by Leuis Hamo, his brother Arvirargus continues the defence, but eventually agrees to submit to Rome, and is given the hand of Claudius’ daughter Genuissa in marriage. Claudius returns to Rome, leaving the province under Arvirargus’ governorship. British kings continue under Roman rule. They include Britain’s first Christian king (Lucius), and several Romans, such as Emperor Constantine I, the usurper Allectus, and military leader Asclepiodotus.

Books V and VI – The House of Constantine

Book V – From the Death of Lucius to the Death of Maximianus

Lucius dies without issue. Severus, a Senator, subdues part of Britain. Carausius is advanced to be “King of Britain”. Allectus kills Carausius but afterward is slain in a fight by Asclepiodotus. There is then an insurrection against Asclepiodotus, by Coel, whose daughter Helena marries Constantius. When Duke Octavius of Wisseans passes the crown to his son-in-law Maximianus, his nephew Conan Meriadoc is given the rule of Brittany (Armorica) to compensate him for not succeeding. After a long period of Roman rule, the Romans decide to no longer defend the island (so they depart). The Britons are immediately besieged by attacks from Picts, Scots, and Danes, especially as their numbers have been depleted due to Conan colonising Armorica and Maximianus using British troops for his campaigns. Maximianus is killed in Rome.

Book VI – From Gratian’s Rule and Murder to Merlin and Vortigern

After Gratian advances to the throne, he is killed by the common people. In despair, the Britons send letters, asking for help from the general of the Roman forces. The Britons receive no reply (this passage duplicates the corresponding section in De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae of Gildas). After the Romans leave, the Britons ask the King of Brittany, Aldroenus, descended from Conan, to rule them. Instead, Aldroenus sends his brother Constantine to rule the Britons. After Constantine’s death, Vortigern assists the eldest son Constans in succeeding, before enabling his murder and coming to power himself. Constantine’s remaining sons Aurelius Ambrosius and Uther are too young to rule and are taken to safety in Armorica. “Saxons” are invited to ally themselves with Vortigern. Although paid mercenaries, they quickly rise against him. Vortigern loses control of much of his land and encounters Merlin (Vortigern having been told by his court magicians that a youth is to be brought to him, a youth who never had a father). Vortigern inquires of Merlin’s mother concerning her conception of Merlin. Advice is then given to Vortigern, by Merlin, concerning the building of a tower.

Book VII – Merlin’s Prophecies

It is here that Geoffrey suddenly breaks his narrative by inserting a series of prophecies attributed to Merlin. Some of these prophecies act as a paradigm for upcoming chapters of Historia, while others are indistinct hints to historical people and events of the Norman world in the 11th and 12th Centuries AD. The rest of the prophecies are very unclear.

Book VIII – The House of Constantine (continued)

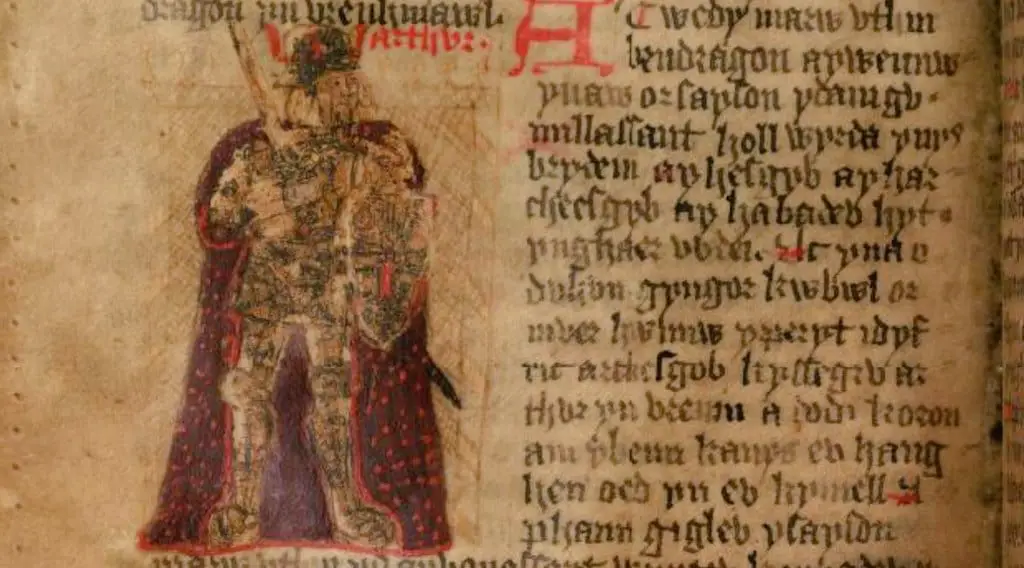

Vortigern asks Merlin concerning his death. After Aurelius Ambrosius defeats and kills Vortigern, burning him in a tower, Aurelius becomes king. Britain remains in a state of war under Aurelius and his brother Uther. They are both assisted by the wizard Merlin. At one point during the continuous string of battles, Ambrosius takes ill and Uther must lead the army in his stead. This allows an enemy assassin to pose as a physician and poison Aurelius Ambrosius. When the king dies, a comet taking the form of a dragon’s head (pendragon), appears in the night sky; which Merlin interprets as a sign that Aurelius is dead and that Uther will be victorious and succeed him. So after defeating his latest enemies, Uther adds “Pendragon” to his name and is crowned king. But another enemy strikes, forcing Uther to make war again. Although temporarily defeated, Uther gains final victory with the help of Duke Gorlois of Cornwall. While celebrating this triumph with Gorlois, Uther falls in love with Igerna, the duke’s wife. This leads to war between Uther and Gorlois, during which Uther covertly lies with Igerna through Merlin’s magic. Arthur is conceived that night. Then Gorlois is killed and Uther marries Igerna. But Uther must war against the “Saxons” again. Even though Uther triumphs, he later dies after drinking water from a spring that had been poisoned by the “Saxons”.

Books IX and X – Arthur of Britain

Books IX – Arthur on the Rise

Arthur, son of Uther Pendragon, takes the throne and defeats the “Saxons” so gravely that they stop being a threat until after his death. In the meantime, Arthur conquers most of northern Europe (including Iceland, Gothland, Norway, Dacia, Aquitaine, and Gaul), and ushers in a period of peace and prosperity that lasts until the Romans, led by General Lucius Hiberius (Tiberius), demand that Britain once again pay tribute to Rome. Arthur, holding council with his sub-Kings, desires each of them to deliver an opinion. They unanimously agree upon a war with the Romans. Arthur prepares for war and refuses to pay tribute to Rome.

Book X – Arthur, as he Falls

Lucius calls together the Eastern Kings against the Britons. Arthur commits to his nephew, Mordred, the government of Britain. Arthur then kills a Spanish giant who had stolen away Helena, the niece of Hoel. The Romans attack the Britons with a mighty army, but they are soundly defeated. Arthur defeats and kills Lucius in Gaul, intending to become Emperor himself. Alas, in Arthur’s absence, his nephew Mordred seduces and marries Guinevere, thereby seizing the throne for himself.

Books XI and XII – The Eventual “Saxon” Domination

Book XI – Arthur’s End, and the Loss of Logres

Arthur returns to Britain. Mordred makes a great slaughter of Arthur’s men, but is beaten and flees to what is now Winchester. Mordred, after being twice besieged and routed, is killed at the Battle of Camlann. Arthur, mortally wounded, is carried off to the Isle of Avalon, and hands the kingdom to his cousin Constantine, son of Duke Cador of Cornwall. The “Saxons” return after Arthur’s death, and, along with the sons of Mordred, are met with battle by Constantine. After having killed Mordred’s sons, Constantine is himself killed by Aurelius Conan (who then reigns afterward as King). Vortiporius is then declared King, followed by King Malgo. The Britons lose their Kingdom of Loegria (Logres).

Book XII – The End of the Kings of Britain: From Cadwallo to Æthelstan

Cadwallo becomes King of Britain. When he dies, he is succeeded by Cadwallader, who is forced to flee Britain and requests the aid of King Alan of the Armoricans. However, an angel’s voice tells him that the Britons will no longer rule and that he should go to Rome. Cadwallader does so, dying there, though he leaves his son and nephew (Ivor and Ini) to rule the remaining Britons. They attack the “Angle” nation but fail. The remaining Britons are driven into what is now Wales and the Saxon Æthelstan becomes King of Loegria (Logres).

Geoffrey’s Sources

Lewis Thorpe, Neil Wright, and Andrew Lang tell us that Geoffrey claimed to have translated Historia into Latin from “a very ancient book in the British tongue”, given to him by Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. Lang goes on to tell of Geoffrey, “He says that he has had the advantage of using a book in the Breton tongue” which Walter brought from Brittany. This book is translated into Latin. Thorpe and Wright, as well as Boydell and Brewer, tell us that no modern scholars take this claim too seriously. Boydell and Brewer continue by saying: “This fusion of heterogeneous sources, which is apparent almost everywhere in the Historia, completely dispels the fiction that the text is no more than a translation of a single Welsh (or Breton) book”. Wright says that Historia Regum Britanniae does not bear serious examination as authentic history and that no scholar today would regard it as history. According to Thorpe, much of the work appears to be derived from Gildas’ 6th-Century AD polemic De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On Ruin and Conquest of Britain), Bede’s 8th-Century Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of English People, or A History of the English Church and People), the 9th-Century Historia Brittonum (History of Britons) ascribed to pseudoNennius, the 10th-Century AD Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales), mediæval Welsh genealogies (such as the Harleian Genealogies), king-lists, the poems of Taliesin, the Welsh tale Culhwch ac Olwen, and some of the mediæval Welsh saints’ lives; all expanded and turned into a continuous narrative by Geoffrey’s imagination and creativity.

Influence of Historia (or De Gestis)

C Warren Hollister tells us that, in an exchange of manuscripts of their histories, Robert of Torigny gave Henry of Huntington a copy of Historia Regum Britanniae. They both used it as a reliable history and afterward incorporated it into their works. In this way, some of Geoffrey’s supposéd fictions became embedded in popular history. Historia forms the basis for much British lore and literature as well as being a rich source of material for Welsh bards. Becoming hugely popular during the High Middle Ages, it greatly modified views of British history before and during the “Anglo-Saxon” period despite the criticism of writers such as William of Newburgh and Gerald of Wales. In particular, the prophecies of Merlin were often used in later periods by both sides in the issue of English influence over Scotland under Edward I and his successors. Historia was quickly translated into Norman verse by Wace (Roman de Brut) in AD 1155. Wace’s version was in turn translated into Middle English verse by Layamon (Brut) in the early 13th Century. In the second quarter of the 13th Century, a Latin verse version, the Gesta Regum Britanniae, was produced by William of Rennes. Material from Geoffrey was integrated into a large collection of Anglo-Norman and Middle English prose compilations of historical material from the 13th Century AD onward.

A O H Jarman tells us that Geoffrey was translated into many different Welsh prose versions by the end of the 13th Century, collectively known as Brut y Brenhinedd (Chronicle of the Kings). One variant of Brut y Brenhinedd, the so-called Brut Tysilio (History of Tysilio), was proposed in 1917 by the archæologist William Flinders Petrie to be the ancient “British” book that Geoffrey translated, although Brut itself claims to have been translated from Latin by Walter of Oxford, based on his own earlier translation from Welsh to Latin, says William R Cooper. Geoffrey’s work is of great importance because it brought the Welsh culture into British society and made it acceptable. It is the first record we have of King Lear and the beginnings of the mythical King Arthur figure. For centuries, Historia Regum Britanniae was accepted at face value, and much of its material was incorporated into Holinshed’s 16th-Century AD Chronicles. Most modern historians have regarded Historia as a work of fiction with some factual information contained within. John Morris in The Age of Arthur, unfortunately, calls it a “deliberate spoof”, although this is based on misidentifying Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, as Walter Map, a satirical writer who lived a century later. Historia continues to influence popular culture of today.

The Manuscript’s History and Its Textual Tradition

Two hundred fifteen mediæval manuscripts of Historia survive, dozens of them copied before the end of the 12th Century AD. Even among the earliest manuscripts, there are a large number of textual variants, such as the so-called “First Variant”. These variants are evident in the three possible prefaces to the work and the presence or absence of certain episodes and phrases. Certain variants may be due to “authorial” additions to different early copies, but most probably reflect early attempts to alter, add to, or otherwise edit the content of the overall text. The task of disentangling these variants and establishing Geoffrey’s original text is long and complex, and the degree of the difficulties surrounding the text has only recently been established. The alternate title Historia Regum Britanniae appeared in the Middle Ages and has become the most common form in modern times. A critical edition of the work, by Reeve, published in 2007, demonstrated that the most accurate manuscripts refer to the work as De Gestis Britonum and that this was the title Geoffrey himself used about his work.

Overall Assessment

It is obvious that De Gestis Britonum, or Historia Regum Britanniae, has a long and varied journey from Geoffrey’s original penning of the text to its present form. Yet, it does contain “grains of truth” that must be “sifted” out of the overall textual tradition. These manuscripts contain the earliest known version of the story of King Lear and his three daughters, and they have helped to popularise the legend of King Arthur. Geoffrey combined the works of Gildas, Bede, and pseudoNennius; as well as various king-lists, genealogies, poems, and saints’ lives. Multiple historians in the Middle Ages used Geoffrey’s words as fact. He helped to make Welsh culture acceptable within British society as a whole; even though the “very ancient book” might well have been of Breton origin. The word used for the “tongue” in which the “book” was written is “Bretagne”. It can easily refer to Welsh or Breton. One can take “Bretagne” even further to connote an ancient group of inhabitants of Britain, the Picts. It is worth noting that the Pictish word for themselves is variously spelled as “Prydyn, Prydain, and Cruithin”. Greeks (and some Romans) referred to the Picts, not only as Picti, but as “Βρίττωνες (Brittones, Brittanni)” and “Πρετ(τ)αν(ν)οί (Pret(t)an(n)oi, Pritani, and Priteni)”. If this mystery of “Bretagne” can be solved, it will help answer the riddle of the true origin of the “most ancient” of Geoffrey’s sources. De Gestis (Historia) is influential even today, as some modern critics attempt to re-examine the text to recover the original form and content of the work. Much effort is still to be put forth upon the entangled tapestry of this “quasi-pseudo-historical account of British history”. Whatever truths are held within, they will one day be brought to light for the benefit of all.