Historia Anglorum (History of Angles, or History of England, or History of English People) by Henry of Huntingdon

Preface and Provenance

“To Alexander, Bishop of Lincoln”

As the pursuit of learning in all its branches affords, it is my considered opinion that the sweetest earthly mitigation of trouble and consolation in grief is to be found almost entirely in the study of literature. So I consider that precedence must be assigned to the splendour of historical writing, as both the most delightful of cherished studies and the one which is invested with the noblest prerogatives and given the most glorious of positions. Is nothing more excellent in this life than the grandeur of heroic men shining brightly, or the wisdom of the prudent, or the discretion of the righteous, or the moderation of the temperate, than in the series of actions which historical context records?

So begins the preface of Historia Anglorum, Henry of Huntingdon’s most notable work, as paraphrased from Thomas Arnold’s edition of Henrici archidiaconi huntendunensis Historia Anglorum; The History of the English, by Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon, from AC 55 to AD 1154, In Eight Books (1879). Henry of Huntingdon (Latin: Henricus Huntindoniensis; AD 1084/1088 – AD 1155/1157), the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-Century AD English historian. C Warren Hollister calls Henry “the most important Anglo-Norman historian to emerge from the secular clergy”. Henry was asked by Bishop Alexander of Lincoln (both Henry’s patron, and also Geoffrey of Monmouth’s) to write a history of England from the earliest period to modern times. Historia Anglorum is that history. The primary language of Historia is Latin. The secondary language is Middle English (AD 1100-1500). It is assumed that the first edition began between April 1123 and 1129, and published by the end of AD 1129. The first seven books, being the bulk of the work, was completed around the date of the latest event which it records (October 1131). The second edition appeared in AD 1135, at the end of the reign of Henry I of England.

Henry of Huntingdon added three more books to the text during the next decade, one of which (Book IX) is a tract about the miracles of England’s saints. He published new editions as the years went on, the final fifth copy (that included Book X) produced in AD 1154, was supposedly to terminate Historia with the death of Stephen. As first conceived, this tenth book extended as far as AD 1138, but the book was extended as the reign unfolded and, in its final form, it concludes with the coronation of Henry II in AD 1154. During these decades, Henry of Huntingdon revisited his earlier books to revise them. There is some evidence that Henry did not intend to stop there, meaning to add another book to his series that would cover the events of the reign of Henry II (only its first five years). It was never carried out, as Henry must have been at least in his late sixties/early seventies by the time of the king’s accession and died shortly afterward (around AD 1155 or 1157). Thus, as Paul Hayward tells us, there survive among the thirty or so manuscripts now extant, as Diana Greenway shows, some six different versions of the text. They correspond to copies taken in c AD 1135 (versions 1 and 2), c AD 1138 (version 3), c AD 1148 (version 4), c AD 1149 (version 5), and c AD 1155 (version 6). Historia was much used by other authors.

The Purpose of Historia Anglorum

This work was written to explain Henry of Huntingdon’s present time, and the earlier history of England, to the less educated (but not the uneducated). As Paul Hayward puts it, Alexander commissioned Henry to “narrate the history of this kingdom and the origins of our people”. For that reason, Historia is a simple and entertaining read, designed both to instruct and entertain. Hayward goes on to say that “as Henry explains in his preface, it was intended to be a convenient work in a single volume, drawn from earlier materials which had for that reason to be heavily abbreviated”. A goodly amount of the narrative of the pre-Conquest era is indeed extracted from earlier works. Henry’s talent for communicating detail is responsible for entertaining touches taken from contemporary legend and his own fertile imagination. C W Hollister notes the anecdote of King Canute’s failure to stem the tide by command and Henry I’s ignoring his physician’s orders to dine on lampreys. Such embellishments made his history popular. There are twenty-five extant manuscripts, and they embedded his anecdotes deeply into the popular consciousness.

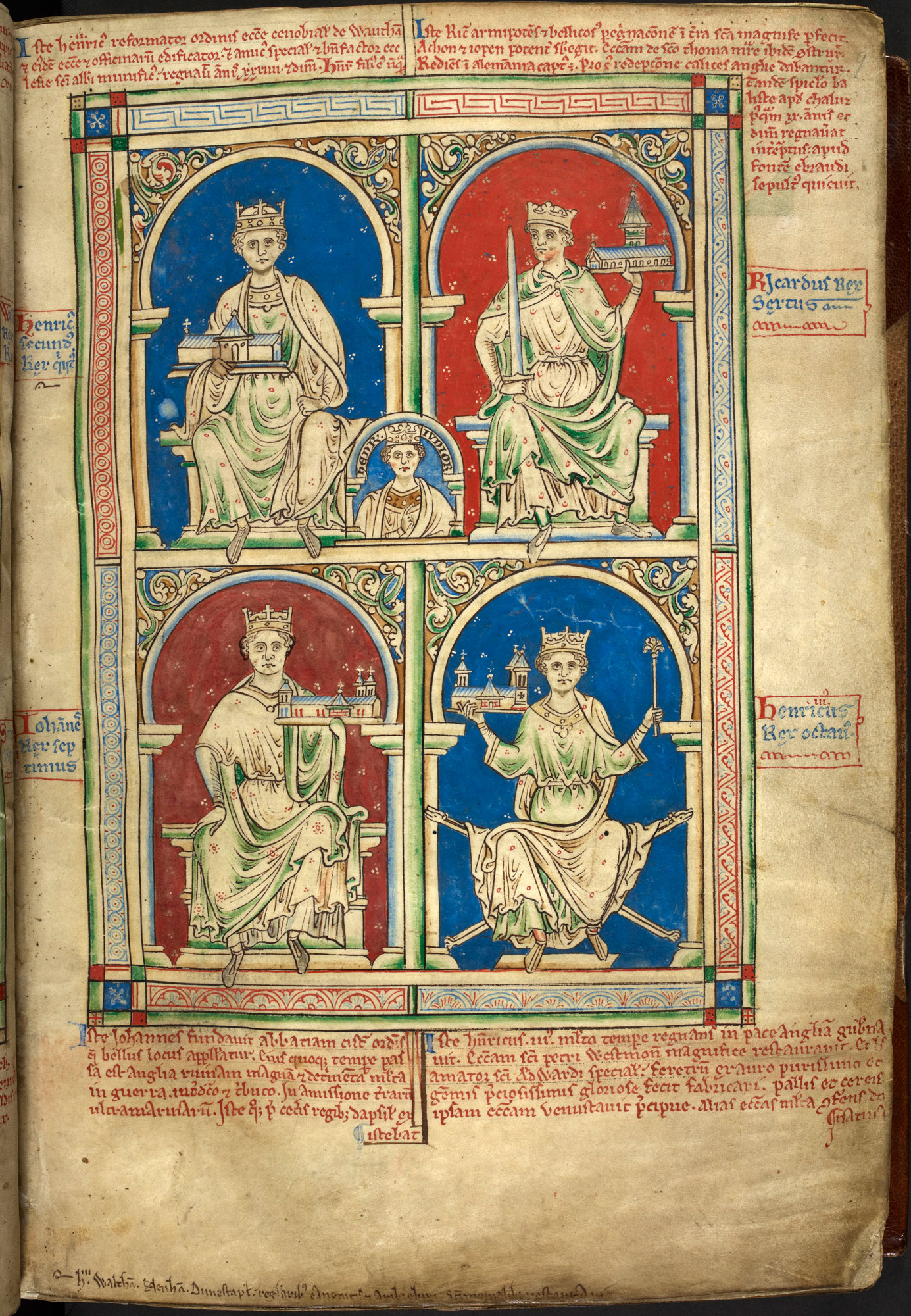

Walters (W.793) Manuscript

Produced in the early (first half of the) 13th Century AD, the Walters MS W.793 is an important textual witness to Historia Anglorum by Henry of Huntingdon. The first version of Henry’s text had an ending date of AD 1129, though there were four more updates containing events through AD 1135, 1138, 1148, and 1154. The Walters W.793 MS represents the fourth version, covering the events from Britain’s first leaders up to AD 1148, in which the number of books was increased from eight to ten, and three self-authored letters were added. W.793’s provenance is most likely Winchester, England. The text contains several coloured foliate initials, though it is especially notable for its line drawing of King Stephen (who died AD 1154), grandson of William the Conqueror, and his earls before the Battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141. The Walters Manuscript is closely related to the British Library’s Arundel MS 48, which is believed to have been the prototype from which W.793 was copied. Both copies may have been based on an even earlier prototype extant during the lifetime of Henry of Blois (who died AD 1171). Of the approximately three dozen surviving manuscript copies of Historia Anglorum, only eight predate W.793. Walters 793 and Arundel 48 are the only known illustrated excellent examples.

Henry’s Sources

Henry of Huntingdon used nine primary sources (or groups of sources, as it were) for Historia Anglorum: Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica, for the years up to AD 731; Historia Brittonum (Vatican recension); Paul the Deacon’s Historia Romana, for the Roman emperors, and Eutropius and Aurelius Victor; the body of works of Saint Jerome and Gregory the Great, with which Henry had a passing familiarity; the Saints’ Lives (especially for Book IX); versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle similar to C and E (including the poem on Brunanburh, which he translated into Latin); a now lost version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which Henry shared with John of Worcester (this version contained a number of detailed and valuable accounts of battles of Saxon invasions of Britain which are only preserved in Henry’s Historia); Old English poems, which Henry translated into Latin (and may include the legend of King Canute and the waves, as well as material on Siward, Earl of Northumbria); and Old French songs, for Norman history.

The Five Punishments

There is a religious element to Historia Anglorum: as both Diana Greenway and Paul Hayward claim, Henry of Huntingdon saw the five invasions of Britain (by the Romans, the Picts and the Scots, the Angles and the Saxons, the Danes, and then the Normans) as analogous with the five punishments from God in the Old Testament, and inflicted on the island’s peoples because of their sinfulness. For that and other reasons, Henry saw the history of England as a progressive continuity rather than disruption and chaos, reflected in the easy passage between chapters and indeed his explanation of the invasions. Paul Hayward tells us that “Henry heightens the drama at key moments, introducing invented speeches into the mouths of Julius Caesar and of William the Conqueror and into his accounts of the battles of the Standard and of Lincoln.”

Arthur as Arthurus

In Book II of The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, Comprising the History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Cæsar to the Accession of Henry II. (1853), translated and edited by Thomas Forester, on facing pages marked AD 508 to AD 514 (after the AD 527 paragraph indicator), paraphrased thusly: In those times Arthur the great warrior, leader of the armies and chief of the kings of Britain, was consistently victorious in his wars with the Saxons. … The first battle was fought near the mouth of the river which is called Glenus (Glenn). … The eighth battle against the barbarians was fought near the (continued on following page marked as AD 527 to AD 530) castle Guinnion, during which Arthur bore the image of Saint Mary, mother of God and always virgin, … The ninth battle he fought at the city Leogis (Legionis, of the legion), which in the British tongue is called “Kaerlion”. … but in our times the places are unknown, …. The same passage, in Book II §18, of Thomas Arnold’s edition of Henrici archidiaconi huntendunensis Historia Anglorum (1879), in Latin, “Arthurus belliger, illis temporibus dux militum et regum Britanniæ, contra illos invictissime pugnabat: … Primum bellum contra eos iniit juxta ostium fluminis quod dicitur Glenus (Glemiz, Glenn) … octavum contra barbaros egit bellum juxta castellum Guinnion; in quo idem Arthurus imaginem S Mariæ Dei Genetricis semperque Virginis … nonum egit bellum in urbe Leogis, quæ Britannice “Kaerlion” dicitur … Quæ tamen omnia loca nostræ ætati incognita sunt; ….”

Thomas Arnold notes that Henry does not appear to have seen any manuscripts of Historia Britonum which ascribed the authorship to Nennius. Among the thirty or more manuscripts still extant, only two or three, and those dating only from the twelfth century, contain the prologues which name Nennius as the author. Being ignorant, therefore, of the real name of the writer whom he was following, Henry seems to have used the term “Gildas” as a general name for a Welsh chronicler, because of the fame which became attached to the memory of Gildas the Wise, author of De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniæ. Similarly, the fame of Marianus Scotus caused his name to be attached to compilations with which he had nothing whatever to do.

Conclusion

Henry of Huntingdon was asked by Bishop Alexander of Lincoln to write a history of England from the earliest period to modern times. Historia Anglorum is that history. This work is comprised of ten books, covering the earliest history up to the coronation of Henry II in AD 1154. Historia was written to explain Henry’s present time, and the earlier history of England, to the less educated (but not the uneducated). Produced in the early (first half) 13th Century AD, the Walters MS W.793 is an important textual witness to Historia Anglorum. Henry used nine primary sources (or groups of sources, as it were) for Historia Anglorum: Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica; Vatican recension of Historia Brittonum; Historia Romana by Paul the Deacon; the body of works of Saint Jerome and Gregory the Great; the Saints’ Lives; versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle similar to C and E; a now lost version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which Henry shared with John of Worcester; Old English poems; and Old French songs.

Religiously speaking, Henry of Huntingdon saw the five invasions of Britain (by the Romans, the Picts and the Scots, the Angles and the Saxons, the Danes, and then the Normans) as analogous with the five punishments from God in the Old Testament, and inflicted on the island’s peoples because of their sinfulness. Continuing the religious theme, Arthur appears as Arthurus in Book II of Thomas Forester’s The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, Comprising the History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Cæsar to the Accession of Henry II. (1853), paraphrased thusly: In those times Arthur the great warrior, leader of the armies and chief of the kings of Britain, was consistently victorious in his wars with the Saxons. … The first battle was fought near the mouth of the river which is called Glenus (Glenn). … The eighth battle against the barbarians was fought near the castle Guinnion, during which Arthur bore the image of Saint Mary, mother of God and always virgin, … The ninth battle he fought at the city Leogis (Legionis, of the legion), which in the British tongue is called “Kaerlion” … but in our times the places are unknown ….

The following is the original Latin from Book II, §18, of Thomas Arnold’s edition of Henrici archidiaconi huntendunensis Historia Anglorum (1879): “Arthurus belliger, illis temporibus dux militum et regum Britanniæ, contra illos invictissime pugnabat: … Primum bellum contra eos iniit juxta ostium fluminis quod dicitur Glenus (Glemiz, Glenn) … octavum contra barbaros egit bellum juxta castellum Guinnion; in quo idem Arthurus imaginem S Mariæ Dei Genetricis semperque Virginis … nonum egit bellum in urbe Leogis, quæ Britannice “Kaerlion” dicitur … Quæ tamen omnia loca nostræ ætati incognita sunt; ….” Thomas Arnold notes that Henry does not appear to have seen any manuscripts of Historia Britonum which ascribed the authorship to Nennius. Being ignorant, therefore, of the real name of the writer whom he was following, Henry seems to have used the term “Gildas” as a general name for a Welsh chronicler, because of the fame which became attached to the memory of Gildas the Wise, author of De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniæ. Even though Henry was ignorant of certain sources in terms of their authorship, he did present an overall religiously motivated history that was easily accessed by the “less educated” of society. Both entertaining and educational, Historia contains the recognisable account of Arthur (Arthurus) as dux bellorum (leader in battle) who wins twelve victories over the “Saxons”, culminating in the Battle of Badon. By Henry’s time, Arthur was a fully mythologised historical figure who was set in an historical timeline (between AD 508 and 530 for the “twelve battles”). Most historians place the Battle of Badon between AD 490 and 517, which does overlap with the timeframe presented by Henry of Huntingdon.