(On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, or just On the Ruin of Britain):

A Sermon in Three Parts

Introduction to Parts One and Two

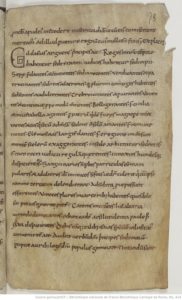

De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae is a work by the 6th-Century AD British cleric Gildas. It condemns the acts of Gildas’ contemporaries, both secular and religious, whom he blames for the dreadful state of affairs in post-Roman Britain.

De Excidio is an important source for the history of Britain in the 5th and 6th Centuries. Part One consists of Gildas’ explanation for his work, and a brief narrative of British history from the Roman conquest to Gildas’ time. It is the earliest source to mention Ambrosius Aurelianus, and the Britons’ victory against the Saxons at the Battle of Badon Hill.

Part Two is a condemnation of five British kings for their various sins, including both obscure figures and relatively well-documented ones such as Maelgwn of Gwynedd. The reason for Gildas’ dislike for these individuals is unknown. He was discriminating in his choice of kings, as he had no comments concerning the kings of the other British kingdoms that were thriving at the time, such as Rheged, Gododdin, Elmet, or Pengwern.

That he chose only the kings associated with one king’s pre-eminence (Maglocune, the “dragon”) suggests a reason other than his claim of moral outrage over personal degeneracy. Neither outrage nor a doctrinal dispute would seem to justify beginning the condemnation of the five kings with a personal attack against Constantine’s mother (the “unclean lioness”).

The Mysterious Constantine and the Familiar Dragon

Simply put, Gildas’ Constantine is obscure. His Damnonia is generally identified with the kingdom of Dumnonia in southwestern Britain, according to John Edward Lloyd and Thomas D O’Sullivan. Instead, Damnonia is more correctly identified with the area of the Damnonii in what is now western Scotland.

Simply put, Gildas’ Constantine is obscure. His Damnonia is generally identified with the kingdom of Dumnonia in southwestern Britain, according to John Edward Lloyd and Thomas D O’Sullivan. Instead, Damnonia is more correctly identified with the area of the Damnonii in what is now western Scotland.

This Constantine is possibly Constantine Corneu, the son of Cado (born c AD 523, died AD 582). Although, he may be of too late a period to have been cited by Gildas. He could, instead, have been Constantine Mor mac Erc (born c AD 483, died c AD 501). Yet that Constantine is a bit too early for Gildas. His Constantine is indeed obscure, mostly due to the confusion of Dumnonia with Damnonia. Maelgwn (Maglocune), King of Gwynedd, receives the most sweeping condemnation and is described almost as a high king over the other kings.

He is well-documented, with the Isle of Anglesey as his base of power over Gwynedd, so describing Maelgwn as the “dragon of the island” is appropriate. His pre-eminence over other kings is confirmed indirectly in other sources. Maelgwn was a generous contributor to the cause of Christianity throughout Wales, implying a responsibility beyond the boundaries of his own kingdom.

He made donations to support Saint Brynach in Dyfed, Saint Cadoc in Gwynllwg, Saint Cybi in Anglesey, Saint Padarn in Ceredigion, and Saint Tydecho in Powys. J E Lloyd claims that Maelgwn is associated with the founding of Bangor.

The Bear and The Lion’s Whelp

Cuneglasse is Cuneglas(s)us or Cynglas of the royal genealogies, the son of Owain Ddantgwyn (White-tooth) son of Einion Yrth (The Impetuous) son of Cunedda Wledig. He is associated with the southern Gwynedd region of Penllyn, and is the ancestor of a later King of Gwynedd, Caradog ap Meirion.

Aurelius Conanus, also called Caninus, cannot be easily connected to any particular region of Britain. John Edward Lloyd suggests a connection between this king and the descendants of Ambrosius Aurelianus mentioned previously by Gildas; if this is true his kingdom may have been located somewhere in territory subsequently taken by the Anglo-Saxons.

J E Lloyd claims that if the form Caninus should be connected with the Cuna(g)nus found in 6th-Century AD writings, the result in the later royal genealogies would be Cynan. David E Thornton claims that, as Cynan, Aurelius Conanus could well be Cynan Garwyn of Powys or his relative Cynin ap Millo.

The Spotted Leopard

Vortiporius (Vortipore, Old Welsh: Guortepir) was a king of Demetia (Demed/Dyfed) who is seemingly well-attested in both Welsh and Irish genealogies. Some say that he is the son of Aircol, others have called his father Erbin Llawir. This is due to discrepancies between the two genealogies.

Some scholars maintain that he is mentioned on a memorial stone bearing an inscription in both Latin and Ogham. The Latin inscription reads Memoria Voteporigis protictoris. The Ogham inscription consists of a Primitive Irish spelling of the name: Votecorigas (claims J E Lloyd).

If the man mentioned in both inscriptions was the same as Gildas’ Vortiporius, we would expect the Latin and Irish forms to have been spelled Vorteporigis and Vortecorigas, respectively. Patrick Sims-Williams says that the difference in spelling has led some to suggest that they are not the same person, though it is possible that they were genealogically related.

Part Three and De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae’s Importance

Part Three is a similar attack upon the British clergy. It begins with the words, “Britain has priests, but they are fools; numerous ministers, but they are shameless; clerics, but they are wily plunderers.” Gildas continues his diatribe against the clergy, but does not explicitly mention any names in this section, and so does not cast any light on the history of the Christian church.

His work is of great importance to historians because it is almost the only surviving source written by a near-contemporary of British events in the 5th and 6th Centuries AD. The usual date that has been given for this work is in the 540s, but it is now regarded as quite possibly earlier, in the first quarter of the 6th Century AD.

Richard Fletcher claims an even earlier date. Accurately dating De Excidio is problematic due to the existence of three Gildases: Giltas or Gildas, who was born c AD 425 and died AD 512; Gildo or Gildas, who was born c 500 and died c AD 564; and Gildas III, known simply as Gildas, who was born c AD 548 and died after 565.

Whichever Gildas he is, he uses Latin to address the rulers he condemns and regards Britons, at least to some degree, as Roman citizens, despite the collapse of central imperial western authority. By AD 597, when Saint Augustine arrived in Kent, what is now England was populated by Anglo-Saxon pagans. The new rulers did not think of themselves as Roman citizens. Dating Gildas’ words more exactly would provide more certainty about the timeline of the shift.