Introduction to the Text

Culhwch ac Olwen is a Welsh story about a hero associated with Arthur and his warriors. The story survives in only two manuscripts: a complete version in Llyfr Coch Hergest (Red Book of Hergest) c AD 1400, and a fragmented version in Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch (White Book of Rhydderch) c AD 1325. It is the longest of the extant Welsh prose narratives.

The prevailing view among scholars, says James J Wilhelm, was that the present version of the text was composed by the early to mid 11th Century AD (AD 990/1100), making it perhaps the earliest Arthurian tale and one of Wales’ earliest extant prose texts, but a 2005 reassessment by linguist Simon Rodway dates it to the latter half of the 12th Century AD. According to Sioned Davies, the title is a later invention and does not occur in the early manuscripts.

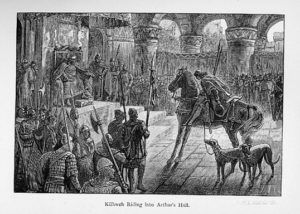

Lady Charlotte Guest included the tale of Culhwch ac Olwen among those she collected under the title The Mabinogion (Mabinogi). Besides the quality of its storytelling, it contains several remarkable passages, three of which are of special importance. The description of Culhwch riding on his horse is often mentioned for its intensity (a passage reused to analogous effect in the 16th-Century AD Welsh prose “parody” Araith Wgon/Wgawn – originally written in the 14th Century AD by the Demetian poet Cadwga(w)n Riiffudd, as well as the passage’s use in 17th-Century AD poetic adaptations of that work). Secondly, the fight against the terrible boar Twrch Trwyth certainly has antecedents in “Celtic” tradition.

Lastly, the list of King Arthur’s retainers recited by the hero is a rhetorical flourish that preserves bits and snippets of Welsh tradition that otherwise would be lost.

Summary of the Plot

Culhwch’s father, King Cilydd, loses his wife Goleuddydd after a difficult childbirth. When he remarries, Culhwch rejects his stepmother’s attempt to pair him with his stepsister. Offended, the new queen puts a curse on Culhwch so that he can only marry the beautiful Olwen, daughter of Ysba(d)dad(d)en (Yspad(d)ad(d)en) Pencawr (Chief/Head Giant).

Culhwch’s father, King Cilydd, loses his wife Goleuddydd after a difficult childbirth. When he remarries, Culhwch rejects his stepmother’s attempt to pair him with his stepsister. Offended, the new queen puts a curse on Culhwch so that he can only marry the beautiful Olwen, daughter of Ysba(d)dad(d)en (Yspad(d)ad(d)en) Pencawr (Chief/Head Giant).

It is said of Ysbadadden that his eyelids were so heavy that they had to be propped up with spears or forks. Though Culhwch has never seen Olwen, he becomes infatuated with her. Culhwch’s father advises him that he will never find her without the aid of his renowned cousin, King Arthur. The young man instantly departs to seek his kinsman. Culhwch finds Arthur at his court in Celliwig in Cornwall.

Patrick K Ford tells us that this is one of the earliest instances in literature or oral tradition of Arthur’s court being assigned a specific location, and a valuable source of comparison with the court of “Camelot” or Caerleon in later Arthurian legends. Arthur agrees to help and sends six of his best warriors: Cai, Gwalchmei, Bedwyr, Cynddylig Gyfarwydd, Menw son of Tairgwaedd, and Gwrhyr Gwalstawd Ieithoedd. (Cai, Gwalchmei, and Bedwyr appear in later legends as Kay, Gawain, and Bedivere.)

The group meets some relatives of Culhwch’s that know Olwen and agree to arrange a meeting. Olwen is open to Culhwch’s advances, but she cannot marry him unless her father, Ysbaddaden, agrees, and he, being unable to live past his daughter’s nuptials, will not give permission until Culhwch completes a series of impossible-sounding labours. The completion of only a few of these tasks is recorded and the giant is killed by Goreu (either the nephew of Ysbadadden or the son of one of Ysbaddaden’s servants), leaving Olwen free to marry her belovéd Culhwch.

The Nature of this “Folk-tale” (Its Motifs and Archetypes)

The story is on one level a typical folk-tale, in which a young hero sets out to wed a (chief of the) giant’s daughter, and many of the accompanying motifs reinforce this (the strange birth, the jealous stepmother, the hero falling in love with a stranger after hearing only her name). Nevertheless, for most of the story, both Culhwch and Olwen are not mentioned. Their story serves as a frame for other events.

The story is on one level a typical folk-tale, in which a young hero sets out to wed a (chief of the) giant’s daughter, and many of the accompanying motifs reinforce this (the strange birth, the jealous stepmother, the hero falling in love with a stranger after hearing only her name). Nevertheless, for most of the story, both Culhwch and Olwen are not mentioned. Their story serves as a frame for other events.

Culhwch ac Olwen is much more than a simple folk-tale. The bulk of the writing is comprised of two long lists, and the adventures of King Arthur and his warriors. This first occurs when Arthur welcomes Culhwch to his court and offers to give him whatever he desires. Of course, Culhwch asks that Arthur help him get Olwen, and brings up some two hundred of the greatest “men, women, dogs, horses, and swords” in Arthur’s kingdom to emphasize his request. Included in the list are names from Irish legend, hagiography (idealized writings of saints or venerated persons), and some from actual history.

Tom Shippey and David Day, as Tolkien scholars, have brought to light the similarities between The Tale of Beren and Lúthien (one of the main cycles of J R R Tolkien’s writings) and Culhwch ac Olwen. In some detail, Shippey says, “The hunting of the great wolf recalls the chase of the boar Twrch Trwyth in the Welsh Mabinogion, while the motif of ‘the hand in the wolf’s mouth’ is one of the most famous parts of the Prose Edda, told of [the] Fenris Wolf and [of] the Norse God Tyr; Huan recalls several faithful hounds of legend, Garm, Gelert, Cafall.”. David Day tells us, “… when these radiant beings – these ‘ladies in white’ – take on mortal heroes as lovers, there are always obstacles to overcome.

These obstacles usually take the form of an almost impossible quest. This is most clearly comparable to Tolkien in the Welsh legend of the wooing of Olwyn [Olwen]. [She] … was the most comely and fair woman of her age; her eyes shone with light, and her skin was white as snow. Olwyn’s name means ‘she of the white track’, so bestowed because four white trefoils [triple-leaved plants] sprang up with her every step on the forest floor, and the winning of her hand required the near-impossible assemblage of the ‘Treasures of Britain’”. Day goes on to say, “In Tolkien, we have two almost identical ‘ladies in white’: Lúthien in The Silmarillion, and Arwen in The Lord of the Rings”.

Conclusions about Culhwch ac Olwen

Besides being one of the earliest (if not the earliest) Welsh Arthurian tale(s) and one of Wales’ earliest extant prose texts, the story contains vivid imagery (Culhwch’s horse-riding, the hunt for the boar Twrch Trwyth, and the recited list of Arthur’s retainers) that survives in later works (such as in Araith Wgawn), and the tale introduces the reader to three of Arthur’s men who are still known to us today (Kay, Bedivere, and Gawain).

This story contains archetypal themes such as a strange birth, the jealous stepmother, and the hero falling in love with a stranger after hearing only her name. The archetype of Olwen herself as “the lady in white” echoes, and is echoed by, that same archetypal figure appearing in the Prose Edda, and Tolkien’s works of The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.

Perhaps, even, Olwen is echoed in the character of Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere) herself, as a “white fairy” or “white phantom”. Keep in mind that Arthur himself, in later legend, does have a “strange birth”; and he does fall in love with Guinevere after only one meeting (or in some tales, after only hearing of her description). Culhwch ac Olwen has far-reaching influences