The arrival of the Saxons into Britain is one of the most important events in the whole history of the British Isles, and in fact, the world. If the Saxons had never taken over control of what is now England, then the entire subsequent history of the country would likely have been completely different. Given the impact that the British Empire had on world history, we can only imagine what the world would look like today if the Saxons had never invaded and the whole course of the island had gone a different way.

Therefore, how the Saxons came to rule Britain is well worth investigating. As with most topics based in Post-Roman Britain, the matter is not a simple one. Let us first take a look at the traditional story of how the Saxons came to dominate the island.

The Traditional Narrative

Sometime after the Romans left Britain, the natives were experiencing harsh raids from surrounding nations, such as the Picts and the Scots. They were ill-equipped to deal with this problem themselves, so the leader of the Britons (a man named in later records as Vortigern), along with a council of some sort, decided to hire Germanic mercenaries to handle the situation.

Sometime after the Romans left Britain, the natives were experiencing harsh raids from surrounding nations, such as the Picts and the Scots. They were ill-equipped to deal with this problem themselves, so the leader of the Britons (a man named in later records as Vortigern), along with a council of some sort, decided to hire Germanic mercenaries to handle the situation.

This is the narrative presented by Gildas, the earliest source for the event, and all later records agree with him. He does not give very much detail regarding how the following events unfolded, but later records, such as Historia Brittonum, are much more specific.

What we gather from Gildas’ brief words and the more extensive information claimed by later sources is this: Vortigern and his council agreed to give the Germanic Anglo-Saxons a portion of land in the south-east of the country in engage for their services. They would also be given supplies of food and other necessities in return.

The mercenaries brought over more of their countrymen with them, and as they continued to do so, their food supplies naturally became inadequate for the continually growing number of people. The Saxons complained about this problem, but the Britons were unwilling to meet the increased demands for food supplies. At this point, the Saxons their broke the treaty that Vortigern had formed with them and started to wage war on the Britons. According to Gildas, this war eventually spread ‘from sea to sea’.

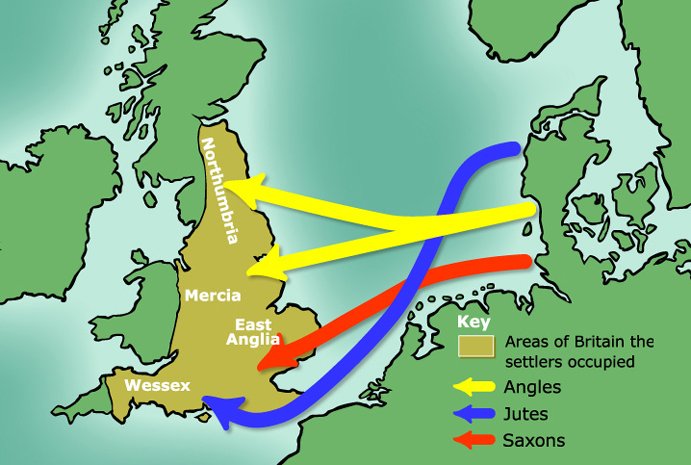

During this time, the Saxons naturally came to control more and more land, spreading out from the south-east of the island. Archaeology has confirmed this, and also that there was an early Saxon presence quite far north, around the area of Lincolnshire. As the Saxons waged their warfare against the Britons, they continually brought over more and more of their fellow countrymen from the continent.

Vortigern himself had a number of dealings with the invaders. Significantly, he was said to have married the daughter of the leader of the Anglo-Saxons, Hengest, and in return he allowed them to have control of Kent.

The British tyrant had a son named Vortimer, who was much more vehemently opposed to the Saxons than his father was. He led the Britons in war against them, fighting a number of battles in Kent. At the third battle, one of the main Saxon leaders, Horsa, was killed.

At the final battle, the Saxons were said to have been pushed back to the sea, Vortimer appearing to have won the war. However, he died shortly after this and his father Vortigern again took the position of leader of the Britons. At this point, the Saxons returned and renewed the war, pushing their way back through the country.

Later, as the war continued, the Britons and the Saxons convened a peace conference, at which the Saxons slaughtered hundreds of British leaders. They spared Vortigern, who allowed them to take Essex, Sussex, Middlesex, and other regions.

The war raged on for years, with the native Britons being scattered about in fear of their enemy. Eventually, a man named Ambrosius Aurelianus united the Britons under his leadership (in opposition to Vortigern) and turned back the tide of the invasion. Vortigern was then killed (though some accounts place his death earlier in the war) and the Saxons were severely opposed by this new leader.

This did not end the war, but it brought about a new phase wherein the Saxons had serious and intense opposition from a newly united army of natives. According to Gildas and other sources, the war raged on more evenly from this point, sometimes the Britons being the victors, and sometimes the Saxons gaining the victory.

Eventually, the fighting led up to a climactic battle at a location called Mount Badon. The Britons were resoundingly victorious at this event. This did not result in the expulsion of the Saxons from the island, but it did completely halt their advance for several decades.

By this point, the Saxons already controlled about half of what is now England. But from the second half of the sixth century through to the seventh, they made significant advances. In 577 they took Bath and Gloucester, right next to the modern-day border of Wales.

In 616, the Anglo-Saxons fought a famous battle against the Britons at Chester, near the current north-east border of Wales. This marks the moment when the Anglo-Saxons began cutting off the Britons in Wales from the Britons in what is now north-west England. Not long after this, the Germanic invaders conquered that remaining corner of the country, finally having control of more or less what is now England.

This is the traditional story of how the Anglo-Saxons came to dominate England – the story that is found throughout the available records, such as Gildas’ De Excidio, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, the Historia Brittonum, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and numerous other records.

A Change in Thinking

However, in recent decades, there has been a shift in thinking towards what really took place in the fifth century. Archaeologists in particular have noted that there seems to be a distinct lack of evidence for bloodshed in this period.

One scholar noted that less than two percent of human remains from this era show signs of violence, which is surely less than what we would expect if essentially the whole nation was at war against the entire nation of Britons.

Furthermore, genetic evidence has been used to firmly argue against the idea of a wholesale massacre of the Britons from Saxon-controlled territory, for pre-Saxon British DNA still makes up a major component of the present-day population of England. This fact is supported by archaeological evidence showing that native British pottery techniques were used among supposedly Saxon settlements in England.

Many scholars have concluded, on the basis of this evidence, that the records of the Anglo-Saxon invasion are greatly exaggerated. Some claim that it should more properly be called a migration rather than an invasion; there were just occasional conflicts and clashes with the natives, but on the whole, it was a semi-peaceful migration of the Germanic tribes into the island. The spread of the Germanic material culture was largely just that: a spread of culture, and not a conquest at all.

There is a minority view that holds that almost no Anglo-Saxons actually migrated at all. Rather, after the end of Roman rule on the island, the natives simple decided to start adopting a Germanic culture. However, this viewpoint is not held by the majority of scholars, who do agree that a large number of Germanics did migrate to Britain.

Nonetheless, it is been the general trend in recent decades to continually play down the level of violence that was likely involved in the Anglo-Saxon migration into Britain. It is certainly no longer considered, by many if not the majority of scholars, to have been an all-out war against the two nations.

Did the Saxons Really Invade?

Despite this recent change of thinking, we would do well to consider the evidence and its possible implications from a more well-rounded perspective. After all, the presence of British techniques in Saxon settlements can be explained in ways other than that the Saxons and Britons peacefully integrated.

Despite this recent change of thinking, we would do well to consider the evidence and its possible implications from a more well-rounded perspective. After all, the presence of British techniques in Saxon settlements can be explained in ways other than that the Saxons and Britons peacefully integrated.

To focus on this supposed piece of evidence for now, consider the fact that historically, in many cultures around the world, male soldiers would often take the female natives as wives after they had conquered a particular area. Once having done that, we can hardly expect that these British women would suddenly forget their methods for making clothing and pottery.

So the presence of British techniques in Saxon settlements fits just as well with the concept of an invasion as it does with a peaceful migration.

Similarly, the fact that the DNA of modern English people is largely made up of pre-Saxon British DNA does not prove that the Saxons did not invade, for mitochondrial DNA passes through the female line. Therefore, these genetic studies could easily be explained by the fact already mentioned, that it would be expected for many British women to have been taken as wives by the Saxon soldiers.

The apparent lack of violence found in the archaeological record is the only serious objection to the traditional narrative of the Saxon invasion, but even this is misrepresented. While a 2% incidence of violence among skeletons may not seem like much, we need to view this in the proper context.

When we remove the remains of women from the equation (for the armies were undoubtedly composed mostly, if not entirely, of men), then this percentage should actually be doubled (since women compose about half of the population) to give us 4% of male remains. And when we remove from the equation all the remains of children that have been found from this period, then that percentage increases even further, perhaps to between 5% and 10%.

So in reality, when we look at the level of violence among the remains of men, those whom we would actually expect to display signs of violence in a time of war, we find that the proportion of skeletons displaying such violence is actually relatively high – 1 in every 10 or 20 men.

In addition to this, many of the men involved in battles would have died on the battlefield and been left to rot or to be eaten by animals. In contrast, the majority of remains that archaeologists uncover are found in grave sites within or near settlements. So it is likely that a very large portion of those slain on the battlefield during the fifth century have simply not been found by archaeologists, leading to the deceptive impression that there was not much violence.

Of course, the archaeological evidence does make it clear that there was not extensive destruction of the British settlements around this time. So clearly the description found in Gildas’ De Excidio is certainly exaggerated, portraying it as if the Anglo-Saxons were a relentless force of destruction that swept across the island.

But, nonetheless, this does not mean that there was not any kind of invasion. The Romans invaded Britain but they did not leave an archaeological record of destruction across the island. Armies were generally beaten away from the settlements, and often the tribes would submit to the invaders’ rulership after their armies (often led by their kings) were defeated in battle.

Similarly, the Romans did not massacre the native population. Many ‘Roman’ towns were almost exclusively populated by native Britons. But nonetheless, the Romans conquered the island and imposed their rulership, material culture and society on the natives. It appears that a similar thing must have happened with the Anglo-Saxon invasion. This understanding would comfortably conform to the archaeological and genetic evidence, while also being in harmony with the written records.

The fact that there really was a large-scale invasion that led to the Saxons taking over control of huge parts of the island is strongly supported by a record from the fifth century known as The Gallic Chronicle of 452. This chronicle, which was evidently completed in the year 452, documents the fact that in 441, the British provinces came under Saxon domination.

Surely, this was not a case of semi-peaceful migration, but was truly a matter of invasion and conquest, just as the later written records universally claim.

When Did the Saxons Arrive?

One more question that surrounds the topic of the Saxon settlement of Britain is the matter of when exactly they arrived. The traditional date is about 447, and the reasons for this are quite clear. Gildas mentioned that the Britons, before hiring the Germanic mercenaries, appealed to a Roman called Agitius for help.

This Roman figure has been identified as Aetius, a Roman consul. This identification is logical, for Gildas refers to Agitius as ‘thrice consul’, and Aetius was consul a total of four times. His third consulship was in 446, and his fourth was in 454. Thus, the reference to Agitius as being ‘thrice consul’ would appear to date the appeal to sometime between those two years.

According to Gildas, after the Romans did not help the Britons to deal with the raids from the Picts and Scots, they were forced to turn to the Germanic mercenaries, as already related. Thus, the arrival of the Saxons into Britain was dated by Bede and many subsequent sources to around the year 447.

However, there are some problems with this chronology. Firstly, the aforementioned Gallic Chronicle of 452 reports that Britain had fallen into the hands of the Saxons in the year 441, which is a full six years before the traditional date of the Saxons’ arrival.

Furthermore, if the invaders had conquered so much of Britain by 441 that it could actually be described as having come under their domination, then the war between the Britons and Saxons must have started a reasonable number of years prior to 441.

In turn, the Saxons were effectively serving as mercenaries for some time before they turned on their employers, which would require the actual arrival of the Saxons to have taken place even further back in time. Therefore, the arrival of the Saxons cannot realistically have taken place any later than the early-430s. Most likely, it was earlier than this.

Supporting the presence of the Saxons in Britain prior to the 440s is another fifth century record. This is the Vita Germani, written in the late fifth century, probably around 480. A visit to Britain by Germanus of Auxerre is described in this record.

One of the events that takes place during the latter part of Germanus’ visit, likely around the year 430, is a battle between the Britons and a joint army of Picts and Saxons.

This places the Saxons in Britain, waging war against the Britons, in the early 430s. This supports the conclusion derived from the Gallic Chronicle of 452, that the Saxons were already in the island and waging war in the 430s.

Interestingly, the Historia Brittonum provides a specific date for the arrival of the Saxons in Britain, and it is not the same as the traditional one derived from Gildas and Bede. This record gives the year as 428. This date is in perfect agreement with the evidence from the Vita Germani and the Gallic Chronicle of 452, both of which are by far the earliest sources for when the Saxons arrived in Britain.

Of course, this would mean that Gildas’ information about Agitius is in error, since the traditional Flavius Aetius is the only man in the fifth century who held the consulship more than twice. Nonetheless, Gildas being in error seems to be the only acceptable conclusion, and there are now some scholars who agree that the Agitius to whom the Britons appealed was most likely not Flavius Aetius, but an earlier individual.

Conclusion

We have seen a number of fascinating things during this discussion. First of all, the entire modern history of the world may well have turned out differently if the British tyrant, Vortigern, had not decided to call on the Anglo-Saxons for help. The face of the island would most probably have looked completely different, with no ‘England’ being formed. The subsequent history of the island would have taken a course that we can only imagine, quite possibly not leading to the British Empire.

We have also seen that there is debate over to what extent the Anglo-Saxons invaded. While there is valid evidence against a wholesale massacre of the native population and a destruction of their settlements, this does not mean that there was no invasion.

Keeping the Roman invasion of Britain in mind when considering the evidence concerning what happened in Britain in the fifth century is helpful, for it shows what kind of evidence we should, or should not, expect. In truth, the evidence is in line with an invasion in the style of the Roman invasion, and the level of violence found in human remains from this period is high when viewed in its proper context.

On the other hand, the traditional understanding of the date of the Saxon arrival in Britain is not supported by the best evidence. In reality, it appears that the Saxons actually arrived in Britain in the late 420s, not the late 440s.

Very informative, there is a basis for some great semi fictional novels there (along the lines of the last Kingdom)

If you know of any please do reccomend them.