Gesta Regum Anglorum, or De Gestis Regum Anglorum

(On) Deeds of Kings of England/(the English),

or (The) Chronicle(s)/History of Kings of England

by William of Malmesbury

Authorship and Content of Gesta

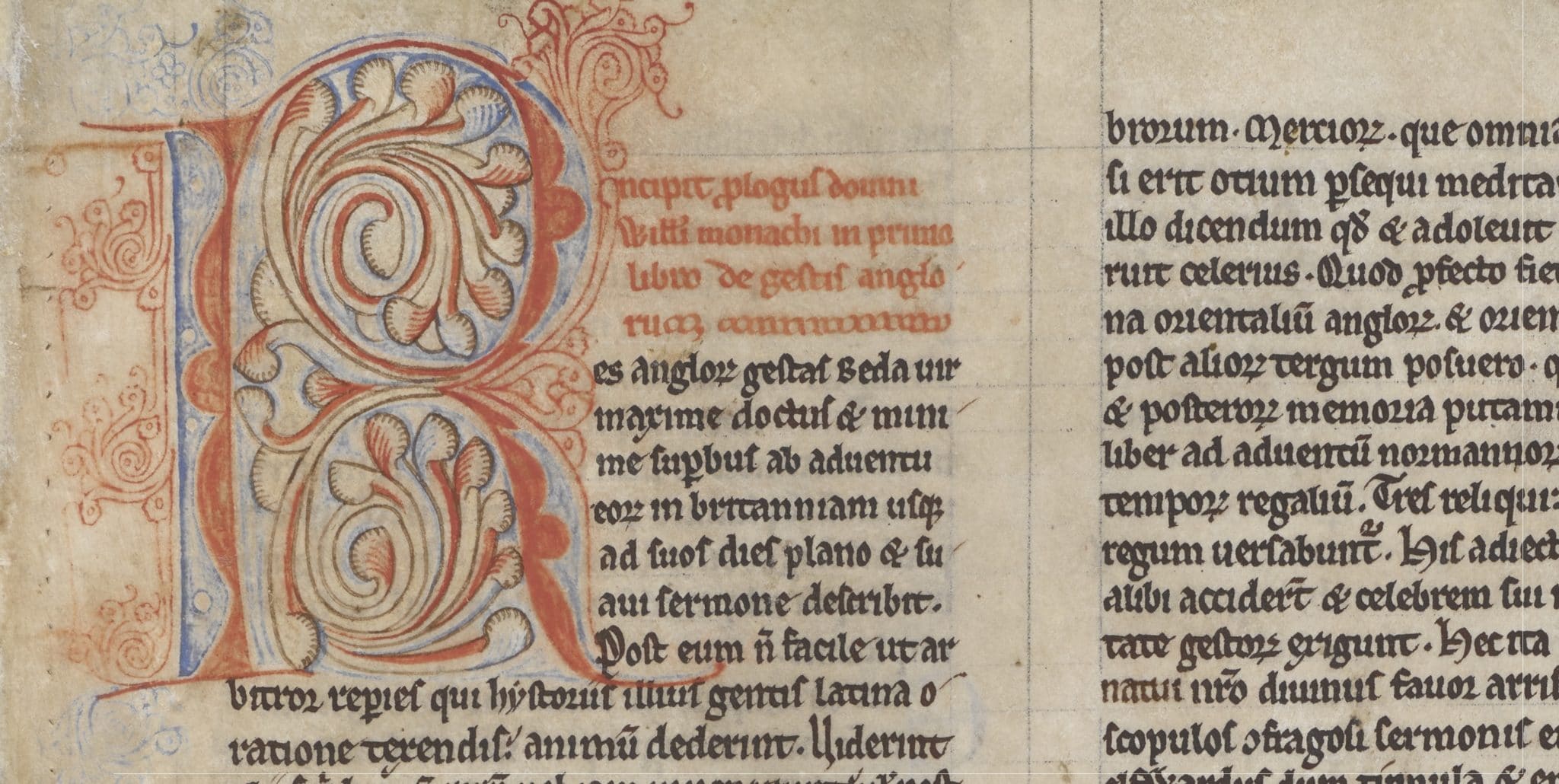

This work is an early 12th Century (AD 1125) history of the Kings of England by an Anglo-Norman cleric, William of Malmesbury (born c 1090, died c AD 1142), a Benedictine monk at Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire, who wrote historical chronicles in Latin in the first half of the 12th Century. Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of Kings of England), originally titled De Gestis Regum Anglorum (On Deeds of Kings of England), is a companion work to William’s Gesta Pontificum Anglorum (Deeds of Bishops of England), and was followed by Historia Novella (Modern History), which continued its event accounts for several more years. William’s respect for the Venerable Bede is apparent within the preface of his Gesta Regum Anglorum, where he professes his admiration for the man. In fulfilment of this idea, according to C Warren Hollister, William completed his Gesta Regum Anglorum, consciously patterned on Bede, which spanned from AD 449 (the Anglo-Saxon invasions) to AD 1120. William later edited and expanded Gesta up to the year 1127, releasing a revision dedicated to Robert, Earl of Gloucester. C W Hollister goes on to tell us that this “second edition” of Gesta Regum, “disclosing in his second thoughts the mellowing of age”, is now considered one of the great histories of England. William of Malmesbury believed that Arthur was an historical figure, but recognised that Arthur’s reputation had been embellished.

References to “Arthur” as Artur

In a combination of paraphrasing from John Allen Giles’ translation of Gesta Regum Anglorum, called William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England, and Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors’, R M Thomson’s, and Michael Winterbottom’s translation called Gesta Regum Anglorum, there are two references to “Arthur”. The first occurs on the pages marked as between AD 449 and AD 520: With Vortimer’s death, the Britons’ strength decayed and withered away. Their hopes dwindled and fled from them. They would soon have collapsed and perished altogether, had not Vortigern’s successor, Ambrosius, the sole surviving Roman, quelled the presumptuous barbarian menace by the powerfully outstanding aid of the warlike Arthur. It is of this hero, Arthur, that the Britons fondly rave in so many foolish fables and wild tales, even to the present day; a man clearly and worthily deserving to be celebrated, not by idle fictions and false dreams, but as the subject of authentic, reliable, and truthful histories (as echoed by Geoffrey Ashe: ‘a man clearly worthy to be proclaimed in true histories’, and by George Pritchard: ‘a man clearly worthy not to be dreamed of in fallacious fables, but to be proclaimed in veracious histories’).

In a combination of paraphrasing from John Allen Giles’ translation of Gesta Regum Anglorum, called William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England, and Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors’, R M Thomson’s, and Michael Winterbottom’s translation called Gesta Regum Anglorum, there are two references to “Arthur”. The first occurs on the pages marked as between AD 449 and AD 520: With Vortimer’s death, the Britons’ strength decayed and withered away. Their hopes dwindled and fled from them. They would soon have collapsed and perished altogether, had not Vortigern’s successor, Ambrosius, the sole surviving Roman, quelled the presumptuous barbarian menace by the powerfully outstanding aid of the warlike Arthur. It is of this hero, Arthur, that the Britons fondly rave in so many foolish fables and wild tales, even to the present day; a man clearly and worthily deserving to be celebrated, not by idle fictions and false dreams, but as the subject of authentic, reliable, and truthful histories (as echoed by Geoffrey Ashe: ‘a man clearly worthy to be proclaimed in true histories’, and by George Pritchard: ‘a man clearly worthy not to be dreamed of in fallacious fables, but to be proclaimed in veracious histories’).

The previous italicised passage, in its original Latin, is thusly: “Hic est Artur de quo Britonum nugae hodieque delirant, dingus plane quem non fallaces somniarent fabulae sed veraces predicarent historiae …”. Arthur long sustained his ailing nation, rousing to battle the broken spirit and shattered minds of his countrymen, and giving them a sharpened edge for war. Finally, at the siege of Mount Badon, relying on an image of the Virgin Mary, which was fastened upon his armour, he did battle with nine hundred of the enemy, single-handed, and routed them with incredible slaughter. In a footnote, it is stated that Badon is Bannesdown, near Bath. Also in the footnote is that Giraldus Cambrensis says that the image of the Virgin was fixed on the inside of Arthur’s shield, that he might kiss it in battle. The same footnote also claims that Bede, in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of English People), erroneously ascribes this event of Badon to AD 493.

The second reference to “Arthur” occurs on the pages marked as between AD 658 and AD 676: For, as we have heard from men of old time, here Gildas, an historian neither unlearned nor inelegant, to whom the Britons are indebted for whatever notice they obtain among other nations, captivated by the sanctity of the place, took up his abode for several years. Contained in the corresponding footnote, it says that there is a Vita Sancti Gildae (Life of Saint Gildas), written not long after this history, by “Caradoc of Lancarvon”, in which we are told, that, while Gildas was residing at Glastonbury, a prince of that country carried off Arthur’s queen and lodged her there; that Arthur immediately besieged it, but, through the mediation of the abbot, and Gildas, Arthur consented, at length, to receive his wife again and to depart peaceably.

Fact and Fiction

Mediæval historians wrote often about Arthur. Siân Echard tells us that some, such as William of Malmesbury, were sceptical. Norris J Lacy states that many of the elements of Arthur’s story were sufficiently fanciful that William lamented the contamination of history by these patent fictions. In so doing, William confirmed both the dramatic expansion of the legend and the belief, which he shared with a good many other chroniclers, in Arthur’s historical existence. Christopher Fee echoes these sentiments in saying that in William’s noting of the plethora of legends sprouting up around the figure of Arthur, William contends that Arthur is a person worthy of the attentions of an accurate historian. Fee goes on to say that Arthur’s great abilities as a warrior and his tremendous devotion to God are detailed by William, who also describes Arthur as a magnificent leader, the heart and soul of the Britons responsible for reviving the shattered martial spirit of his countrymen, a role which culminated in the mighty British victory over the marauding Saxons at Mount Badon. Based in large part upon Historia Brittonum (History of Britons), Gesta Regum Anglorum describes Arthur as a dux bellorum, ‘warlord’ or leader of the British under King Ambrosius, who had succeeded the ill-fated Vortigern. Richard Barber tells us that William of Malmesbury is clearly contrasting the historical account he had found in Historia with much more romantic fictions that he had also encountered.

Arthur’s Grave, Gawain’s Grave, and William’s Visit to Glastonbury

Caitlin R Green states that William of Malmesbury mentions that ‘Arthur’s grave is nowhere to be seen, whence antiquity of fables still claims that he will return’. Richard Barber continues this line of thought by saying that William knows of the legend that Arthur will return, for in discussing the recently discovered tomb of Gawain on the Pembrokeshire coast, William says that Gawain was Arthur’s nephew, and adds: ‘But the grave of Arthur is nowhere to be seen, whence the ancient tales fable that he is to come again.’ We can identify William’s source as Englynnion y Beddau (Stanzas of The Graves), also known as Beddau Milwyr Ynys Prydain (Graves of Warriors of Isle of Britain). Perhaps there was not much more that William knew which has not already survived. Adrian Gilbert tells us that in AD 1125, William of Malmesbury spent some months in Glastonbury. He stayed as a guest at the Abbey, making use of its extensive library while researching his Gesta Regum Anglorum. While there, he was happy to repay the monks’ hospitality by carrying out some researches on the history of their church.

Textual Variants

Four main variants of William’s text have been identified, and one version contains some additions that are believed to have been made by the author himself. Two manuscripts copied between AD 1175 and 1225, both from important English monastic libraries, contain these additions. One, now in the British Library, was in the cathedral priory of Saint Andrew in Rochester in the late 12th/early 13th Century AD and was probably copied there. It contains another historical work by William, Gesta Pontificum Anglorum. The name, ‘Alexander Precentor’ is written on the first page of Gesta Regum next to the ownership inscription of Rochester priory. A precentor was a monk who usually performed the choirmaster duties, those of an archivist, and also a librarian. He took care of the community’s books, which were kept in chests. Another copy of Gesta Regum Anglorum is in a book from Saint Albans abbey. The text is embellished with exquisite small initials containing a dragon, a lion, and other creatures.

Conclusion

Gesta Regum Anglorum, originally titled De Gestis Regum Anglorum, is a companion work to William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Pontificum Anglorum and was followed by Historia Novella. There are two references to “Arthur” (referred to as “Artur” in William’s original Latin text). The first occurs on the pages marked as between AD 449 and AD 520: With Vortimer’s death, the Britons’ strength withered away. Their hopes dwindled. They would soon have perished altogether, had not Vortigern’s successor, Ambrosius, quelled the barbarian menace by the aid of the warlike Arthur. It is of this hero, Arthur, that the Britons fondly rave in so many wild fables, even to the present day; a man clearly deserving to be celebrated, not by idle fictions, but as the subject of authentic histories. Arthur long sustained his ailing nation, rousing to battle the broken spirit of his countrymen, and giving them an edge for war. Finally, at the siege of Mount Badon, relying on an image of the Virgin Mary, he did single-handed battle with nine hundred of the enemy and routed them with incredible slaughter. In a footnote, it is stated that Badon is Bannesdown, near Bath; and that the date of AD 493 is erroneously ascribed to the event of Mount Badon.

The second reference to “Arthur” occurs on the pages marked as between AD 658 and AD 676: For, as we have heard from men of old, here Gildas, an historian to whom the Britons are indebted for whatever notice they obtain among other nations, took up his abode for several years. Contained in the corresponding footnote, it says that there is a Vita Sancti Gildae, in which we are told, that, while Gildas was residing at Glastonbury, a prince of that country carried off Arthur’s queen and lodged her there; that Arthur immediately besieged it, but, through the mediation of the abbot, and Gildas, Arthur consented, at length, to receive his wife again and to depart peaceably. Many of the elements of Arthur’s story were sufficiently fanciful that William of Malmesbury lamented the contamination of history by these fictions. In so doing, William confirmed both the dramatic expansion of the legend and the belief in Arthur’s historical existence. Arthur’s great abilities as a warrior and his devotion to God are detailed, and Arthur is described as a magnificent leader. Based in large part upon Historia Brittonum, Gesta Regum Anglorum depicts Arthur as a dux bellorum, Warlord (“Wledig”) of the British under King Ambrosius, who had succeeded Vortigern. Gesta Regum contrasts the historical account found in Historia Brittonum with much more romantic fictions. There are claims that ‘the grave of Arthur is nowhere to be seen, whence the ancient tales fable that he is to come again’. But which “Arthur”? And when? Only time will tell.